When we think of the First World War it is very easy to forget that it was a global conflict in more than one sense. Our Anglo-centric view of the First World War is often of the mud and blood of the Western Front and very often we consider it to be a World War because of the alliances involved and we very often forget about the fighting within areas of the world that were colonies of the empires. We also often forget of the men and women of the dominions and colonies who found themselves thousands of miles from home fighting for the empires to whom their colonies and dominions at that time belonged. It is also very easy to forget that this service in the First World War included men and even women of the First Nations peoples of Australia, Canada and New Zealand. A walk through a Commonwealth War Graves Commission cemetery does not help dispel this, you get a name, and unit and which dominion nation that unit belongs, but little else about the person buried there. (This is not a criticism of the Commonwealth War Graves Commission as the commission’s charter included that all were to be commemorated equally.)

This service does not mean that it was easy for First Nations men to enlist, enlistment laws in Canada, New Zealand and Australia created issues for some of those wanting to serve, as generally enlistment of First Nations peoples was discouraged or forbidden in the early days of the conflict.

“Aboriginal soldiers of the Canadian Expeditionary Force (CEF) along with elders, ca. 1916–17” Image and description – R. Scott Sheffield – https://opentextbc.ca/postconfederation/chapter/6-12-status-indians-and-military-service-in-the-world-wars/

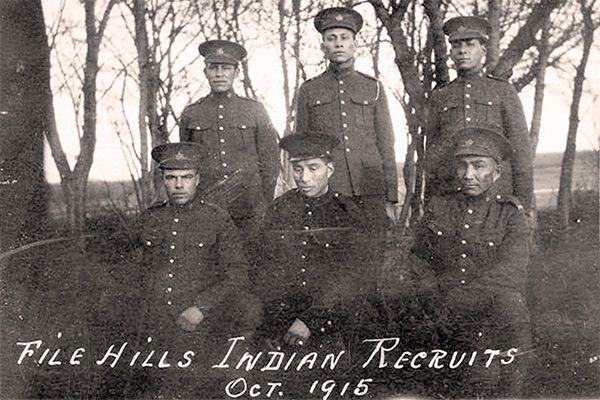

In Canada this was a complicated picture with men from non-status First Nations people, under the Indian Act of Canada, such as men of Métis Nation, could enlist. In addition men from Inuit communities could also enlist. Whereas men from the First Nations covered by the Indian Act were discouraged from enlisting, in a conflict between two European powers. But this discouragement did not last long. Some First Nations men covered by the Indian Act were able to enlist into regular Canadian Army units at the very first days of the war, most likely through recruiters with a more than liberal interpretation of their recruiting instructions. By 1915 formal acceptance of the recruitment of those defined as Status Indians in the Indian Act was allowed, and by 1917 recruitment on reserves and then conscription, which was a contentious issue due to Status Indians not having the full rights of a Canadian Citizens and British Subjects.

Unfortunately, there are only estimates as to how many Canadian First Nations men enlisted in the Canadian Army in the First World War, but of those we can estimate 4000 men, one third of all men between 18 and 45 of status Indians were enlisted into the Army, as only that group were officially recorded, and only when they had not serendipitously enlisted. But it is known that First Nations soldiers served in every battle in which Canadian troops were involved, in units with Canadians of all other backgrounds. As with battles, and conflict, many were wounded, injured and died as either a direct result of action with the enemy, of wounds or of illness and these men are commemorated by the Commonwealth War Graves Commission.

Unfortunately, we only know of a few of their stories.

Lance Corporal John Shiwak, was an Inuit from Labrador, he served with the Royal Newfoundland Regiment. He was born in 1889 in Rigolet, and he was a trapper for the Hudson Bay Company before the war. He enlisted in the 24th July 1915, in St. John’s, Newfoundland. He trained in Canada and Scotland before disembarking at Rouen on the 10th July 1916. On the 24th July 1916 he found himself at the frontline for the first time. His trapping and hunting skills soon pointed him to be a marksman. But on the 21st November 1917, during the Battle of Cambrai , John Shiwak was killed by an exploding shell. He is commemorated on the Beaumont-Hamel (Newfoundland) Memorial.

Sergeant Leo Bouchard was born in 1896, he was from a band that were in the area of Nipigon. Before the war, he had worked as a guide. He enlisted on the 31st May 1915. During the time in the Canadian Army, he served in the 52nd Battalion. During this service he was wounded twice, by gunshot wounds. In the 28th April 1917 his records state he was promoted to Corporal and only a few months later his records state that he was promoted to Sergeant on 24th November 1917. He was awarded the Distinguished Conduct Medal in the London Gazette of the 1st January 1919.

His citation reads :

For conspicuous gallantry and devotion to duty. He has served with his battalion continuously for nearly three years. He has at all times shown marked personal courage, initiative, and skill in handling his men, particularly during the heavy fighting of August, 1918. On one occasion, when his officer was killed, he assumed command, and, though isolated from the rest of his company and in the midst of a dense fog, he led his men through the enemy barrage to their objective.

[https://www.thecanadianencyclopedia.ca/en/article/leo-bouchard]

He was discharged from the Canadian Army in 1919.

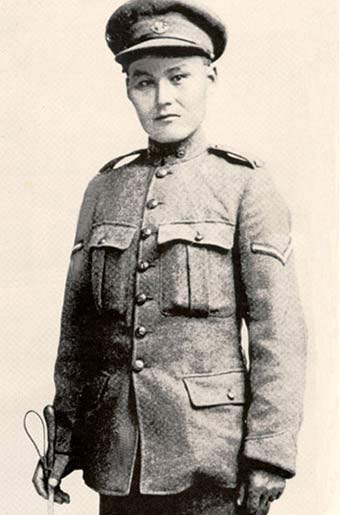

Due to many First Nations men lacking formal qualifications, many were unable to gain commissions, but some did later in the war, when merit and battlefield leadership could allow a soldier a place to train as an officer.

Some did manage to make the standards required at recruitment such as Captain Alexander George Edwin Smith was born in the Six Nations Reserve in Ontario in 1880. He was married before he commissioned as a 2nd Lieutenant and he was contractor before the war. He was wounded several times and due to explosions he suffered hearing difficulties. In October 1916 he was awarded the Military Cross. He was demoralised at the end of the conflict.

Another who met the education standards was Oliver Milton Martin, a pre-war teacher. He was commissioned as an officer, having previously been a private in a militia unit. As a Lieutenant he earned his pilots wings in the Royal Flying Corps. At the end of the First World War he returned to teaching and maintained links with his local militia unit, which in 1930 he began commanding. In the Second World War as a Colonel he was responsible for a training camp. He retired in 1944 having commanded a Brigade as a Brigadier, the highest rank ever held by an indigenous man.

Although only making up a percentage of the men of the Canadian Army, their service and bravery should not be forgotten, nor over looked or glossed over. Even this post is a snapshot of the men and their lives. It is easy to forget just what difficulties these men had to navigate to serve and the cost that their service and sacrifice placed on their communities.

As a Canadian it’s brilliant to see the sacrifices of the First Nations communities being recognised outside of Canada. So many things were wrong about the treatment of the First Nations and Indigenous peoples in Canada, but their service must be acknowledged by all Canadians and those in the United Kingdom as our former Imperial Rulers, as part of the truth and reconciliation and restoration of those First Nations and Indigenous Cultures, as it is a part of our history that is shared and something we all should be proud of.

LikeLike