As we approach the 80th Anniversary of VE Day and VJ Day, days that were celebration for the public at the end of the European and Asian phases of the war. It will be hard not to be swept up in the parades and the pageantry of the events in London and around the globe, as well as street parties and beacon lightings more locally and other events that are planned. But at the same time we should spare a few thoughts, we should spare a thought for those who were still fighting in Asia against the Japanese who were preparing for the prospect of an invasion of Japan and for those who were captives of the Japanese, both civilians and Prisoners of War, who would have months more in captivity, some of whom will still be with us, for whom the anniversary of VE Day will bring back particularly powerful and painful memories. We should spare a thought for those who VE Day brought no news for their missing loved ones, for those who felt the price of war and for whom celebrating would be tinged with loss, and also for those who’s jobs were not complete with the Nazi surrender, who would administer the trials and hurt for the war criminals, as well as preparing for the Cold War. But most of all we should remember that this victory and the Victory over Japan came at a huge cost. This cost came from all over the Free World, from Britain, the now Commonwealth of Nations, the Free Forces of the Occupied Nations and the then USSR.

For the British and Commonwealth of Nations, this cost can be seen through the work of the Commonwealth War Graves Commission. The then Imperial War Graves Commission had within its remit all in uniform who fell or died in service. Added to their responsibilities was the creation of the Civilian War Dead Roll of Honour, which when complete with approximately 70,000 names, was placed in Westminster Abbey. This Roll of Honour highlights the cost that the civilian population paid in the course of the war. Some of these dead were factory workers, some had never worn a uniform before. Some were elderly, and some had barely started life. One that sticks in my mind is Elizabeth Maud Turner, a 16 year old girl, who was working as a cook in the NAAFI at RAF Waddington, who was killed in a German raid on RAF Waddington.

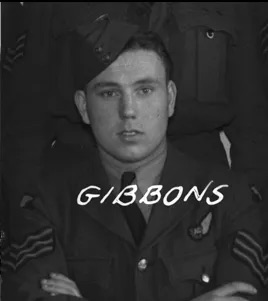

Some men fell in training, this was especially common for those in the Royal Air Force. The losses in conversion units, where the men went after initial flying training to convert to heavy bombers and larger aircraft, were particularly high, especially through accidents. One such was Sergeant Isaac Gibbons, a native of County Durham, probably the furthest from home that he had ever been, was in the 5th Operational Training Unit, which was a feeder for Coastal Command. His B-24 Liberator, which was most likely preparing for operations in the Pacific and Asia, crashed on Welsh Peak in British Columbia, and he was lost along with the rest of the crew. He is commemorated on the Ottawa Memorial. He was 19 years old and left no family except his parents.

Some men fell at sea, when ships were lost. Ordinary Telegraphist Simon McCallum, another native of County Durham, was serving on HMS Southampton, when the ship came under attack by JU.87 Stukas close to Malta. The Stukas caused serious damage, with fire raging the whole length of the ship. This fire prevented many men from escaping the stricken Southampton. 81 men were killed, with the stricken HMS Southampton eventually sunk, after all hope of survival of the crew was lost, by British torpedos. Simon McCallum was 20 years old and survived by his parents.

Some men were lost on land in action with the enemy, one such was Private George Gascoigne of the 2nd Battalion Gordon Highlanders landed in Normandy on the 23rd June 1944. Another native of County Durham, and a pre-war joiner in an explosive factory, mainly creating explosives for mining purposes. The 2nd Battalion Gordon Highlanders were quickly involved in heavy fighting. George Gascoigne died aged 24, was buried at Bayeux War Cemetery and was survived by his Mother, Sister and Brothers.

Some men were lost while in the air. Flight Lieutenant John Morgan Barass, the son of a factory owner, had been commissioned into the Royal Air Force. After much training he was attached to 166 Squadron Royal Air Force. Flight Lieutenant John M Barass had been married to Jean in 1936 in St Paul’s Church Haswell, to much pomp as from a prominent local family, his wedding made the local newspapers. He took off, piloting a Lancaster Mk 1, PD397, from RAF Kirmington for an operation to Koln (Cologne) at 2:50pm on the 24th December 1944. At 6:35pm 24th December 1944, while close to the target area he and his crew were engaged by units of the 7th Flak Division, causing a direct hit. Lancaster PD397 crashed, killing all but one of the crew, with the rear gunner becoming a Prisoner of War. Flight Lieutenant Barass, aged 33, was buried in Rheinburg War Cemetery and was survived by his wife and parents.

Of these who died in service many were buried as quickly as it could be organised. After D-DAY, at Bayeux and Ranville the task of preparing the crosses for the fallen and commemorating the individual by painting the names of the fallen on them, fell to a small group of skilled sign writers, which included Harry Rossney, a half-Jewish German Refugee, who had volunteered for the British Army, and swore his allegiance to King George VI. When interviewed the pain of counting the cost had not faded from 1944 till the day he died. In the course of the years of 1944 and 1945, Harry painted thousands of names onto the crosses, and their incredibly young ages, all personalising the cost of this war and the victory.

During the almost 6 years of the Second World War, almost 600,000 service personnel from the British Empire and Commonwealth and other volunteer nations died and are commemorated by the Commonwealth War Graves Commission. Many of these were sailors and airmen who fell at sea. In line with the then Imperial War Graves Commission’s aims and responsibilities, they either buried or, when there was no known resting place, inscribed the names onto specially constructed memorials. The term Silent Cities dates from a description of the Commonwealth War Graves Commission by Rudyard Kipling who termed the CWGC as the Builders of the Silent Cities. For the Second World War dead, there were 559 cemeteries constructed by the Commonwealth War Graves Commission, as well as burials in some existing sites, as well as the 36 new memorials to those that have no known grave. This is addition to the countless cemeteries in the United Kingdom that have individual graves.

So despite VE Day and VJ Day being days of celebration, remember that this celebration came at a huge cost, and please take a moment to remember the lives lost and lives changed though the course of the Second World War, because it touched communities of all parts of the United Kingdom and beyond and impacted people of all faiths and ethnicities within the United Kingdom and the Commonwealth and is part of the common history of humanity.

We Will Remember Them