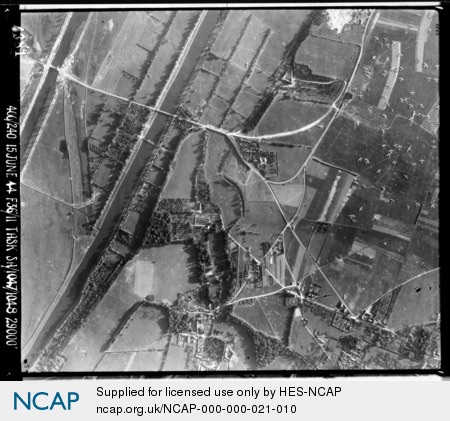

Key to the success of the D-Day Landings, and the Battle of Normandy, was denying the enemy bridges, to prevent them from reinforcing the beaches or counterattacking. Equally key to the success, was the Allies breaking out from the beachhead, this required holding selected bridges. The British had to capture two bridges and hold them against the enemy until reinforced by units that had landed at Sword Beach. The bridges were the Caen Canal Bridge and the Orne River Bridge.

The men of D Company, 2nd Battalion the Oxfordshire and Buckinghamshire Light Infantry, along with some attached Royal Engineers, had been trained for glider operations. Major John Howard, and his men, as part of the 6th Airborne Division, were to be the first men of the D-Day forces to set foot on French soil.

The take-off order was given to the gliders of the 6th Airborne Division at 10:40PM. They began their journey from RAF Tarrant Rushton, towed by Halifax Bombers of the Royal Air Force. Through the skill of the Royal Air Force pilots and navigators, the gliders were released at the right time and place.

At 00:16 the first glider, containing Major John Howard and Lieutenant Herbert Denham (Den) Brotheridge, along with 26 men and two pilots, careered at almost 80mph into the spit of land between the Caen Canal and the Orne River, landing just yards from the bridge, due to the skill of the glider pilots of the Glider Pilot Regiment. These landings were not a safe affair, as Major Howard recounted.

“The door opposite me seemed to collapse in on itself as we came to a halt and the tremendous impact caused me to pass out. As I came round, I found to my horror that I couldn’t see anything. For a frightful second I really believed that I might have been blinded, and then just as quickly realised that my helmet, the battle-bowler, had rammed itself down over my eyes as I hit the roof or the side of the glider. Pushing it up I took in my surroundings – the smashed doorway, the air full of dust, the holes torn in the sides of the glider and the sound of the pilots groaning in the smashed cockpit. And then the glorious realisation came to me, that otherwise there was silence, complete silence, no gunfire at all – we had achieved our first objective of complete surprise.”[1]

Within minutes the second and third gliders landed, joining Major Howard on the spit of land. Lance Corporal Fred Greenhalgh, of the third glider, died on impact, with the glider pilot Staff Sergeant Geoff Barkway, being hit by a burst of fire later in the action, almost totally severing his arm. In all between the two targets, there were six gliders.

The scene was indescribable, men piling out of broken gliders, immediately into the fray as the enemy began to regain composure. Within minutes, Lieutenant Den Brotheridge, already limping from a landing injury, which is now believed to be a broken leg, led his men in a dash across the canal bridge, leading his men from the front. In this dash, a German machine gun opened fire, striking Lieutenant Brotheridge in the neck, mortally wounding him. Hours before the landing craft splashed ashore, the Allies had their first combat casualty.

The landings began a race against time to capture the bridges before the Germans could detonate the pre-planted explosives. As the men of the Oxfordshire and Buckinghamshire Light Infantry rushed forward, the attached men of the Royal Engineers, removed the explosive threat.

In the 10 minutes of action, the 181 men, with only one junior infantry officer still in action, who was himself injured, had captured the bridges. The code words, of Ham and Jam, were broadcast to the Allied Command.

Then began the task of holding the bridges for many hours. The men of the Oxfordshire and Buckinghamshire Light Infantry were joined by the 7th (Light Infantry) Battalion the Parachute Regiment. The men of the 7th Battalion the Parachute Regiment landed at Bénouville and fought their way to eventually join up with Howard’s men at 3AM. The 7th Battalion the Parachute Regiment, had in its number some individuals of note, the actor Richard Todd, a Captain at the time, and Sidney Cornell, a private, eventually a Serjeant, receiving the Distinguished Conduct Medal, the British Army’s first black paratrooper. The Germans began a series of counterattacks. The Luftwaffe attempted to destroy the bridge in an air strike. There was an attempt with a gunboat to recapture the bridge, which was repulsed. The lightly armed airborne forces also repulsed attacks by tanks. The men were joined at 1PM by Lord Lovat, his commandos, and Piper Bill Millin, who had piped the commandos from the landing craft at Sword Beach, all the way to the bridge. At 9PM they were relieved by the advancing infantry from Sword Beach.

The men who fell are buried in the Commonwealth War Graves Commission’s Ranville War Cemetery, and Ranville Church Yard, along with many of the Parachute Regiment and the Oxfordshire and Buckinghamshire Light Infantry that fell in subsequent days. The actions of these men prevented the Germans from derailing the landings and gave the British the vital bridgehead to move forward. The Caen Canal Bridge was immediately renamed, Pegasus Bridge. When the new wider crossing was installed in 1994, the original was moved to form a museum, and the new bridge bears the same name.

[1] Howard, Major John and Howard Bates, Penny. The Pegasus Diaries. Barnsley, South Yorkshire: Pen & Sword Military, 2006.